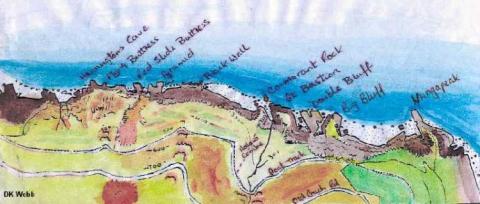

The Exmoor Coast

Traverse 1978.

This site does not contain route information and should not

be used as a guide. What appears to be

access routes on the photographs may not be the case. It is also possible that

the feature may no longer exist. Very

little of the route or the access/escape routes are visible from the cliff top

and are virtually impossible to locate without prior information. On flood

tides both the width and height of the

route corridor shrinks at an alarming rate.

Seek advice before descending these cliffs. Climbing is

dangerous.

The Exmoor Coast Traverse is NOT part of The South West Coast

Path.

At 40ft the tidal range along the length of

The Exmoor Coast is the second highest in the world, crashing against the

highest sea cliffs in England. It is being between these two heavyweights of

nature with no obvious avenue of escape that in my opinion makes The Traverse

the ultimate adventure experience.

Although

the route does not require a high degree of climbing skill, the extreme tidal

conditions, route finding, changeable Exmoor weather and tides, and overall

length make this route a very serious undertaking. The lack of escape routes

causes a great deal of concern. It

should not be undertaken without reference to the tide tables and weather

forecast, both of which are predictions not a certainty. No matter how skilful

you are it will be the natural elements, which decide if you will be

successful, or not. A party of four

should expect to be on the route for four and a half days. This site consists

of some original photos plus later ones donated by explorers of The Exmoor

Coast.

Climbing on

The Exmoor Coast has as much history attached to it as any other climbing area

in the British Isles, but it remains a largely unknown area because of access

problems due to the tidal range and high cliffs. Strangers to the area find

that whole days are wasted trying to locate the routes down the convex hog back

cliffs and many turn up on unsuitable tides. Some state that getting down to the

beach and back is enough for one day.

Underneath

The Hangmans mining had taken place since the 1700’s. Judging from the location

of many of the adits and remaining paths the miners and prospectors would

certainly have climbed on the cliffs.

One of the

earliest climbs recorded on a British sea cliff was Scrattling Crack at Baggy

Point by Tom Longstaff during 1898. Baggy Point is but a few miles west of The

Exmoor Coast. But before in 1869 James Hannington was climbing on the cliffs

below Martinhoe.

severe grade. It was however the remainder of his short life and martyrs death that made him famous

throughout the world. A couple of his paths are marked on old OS maps. More.

The

Victorians were attracted to The Exmoor Coast by its stunning scenery with

large coastal waterfalls and huge cliffs plunging directly into the sea.

Lynmouth became known as Little Switzerland. Their paths to the various

viewpoints can still be found in the undergrowth.

Porlock

to Boscastle which he set out to test.

This would mean finding a route through the section from Lynmouth to Combe Martin,

which Arber had declared inaccessible. Many conventional climbers in the early

60’s must have smiled at Archer’s victorian style with nailed boots and ice

axe. Modern climbers on the traverse have learnt that an axe is essential if

you wish to escape up the 800 – 1000ft cliffs. Many I am sure would also have

preferred to have tricouni nails on their boots on the vertical grass of some

of the escape routes. Archer is the connection to the existing local climbers

on The Exmoor Coast. I was his neighbour and 11years old when he started his

quest. I was allowed to follow him around Exmoor reading his weather

instruments but he would not take me climbing. Kes and Tim Webb were teenagers

and qualified as sherpa’s on his expeditions. Archer was not a good climber, he

was forced to swim past many of the obstacles. At Baggy Point he enlisted the

help of retired Admiral Keith Lawder who went on to open up the North Devon,

Lundy and Cornwall cliffs to climbing. He also met Cyril Manning and Pat Harris

at a talk he was giving about the coast. Archer published a guide, Coastal

Climbs in North Devon, there are a few still around. It is the basic guide for

those who wish to follow his route along the coast. Authors of subsequent

conventional guidebooks have only managed to devote one paragraph to the

traverse. Probably because modern climbing has moved away from the intense

pioneering form of the sport. We pick

up our guidebook and find our adventure already packaged for us. All we have to

do is get there and do it, usually complaining bitterly about a small error the

author has made. Archer was an eccentric, pedantic and very impatient man. He

had been known to throw his tangled rope into the sea. But he was driven to

complete his quest and in doing so has given us a route that takes us back to

the basic sport of man against the mountain and the elements, where the

participants can only blame themselves for errors that occur.

Archer’s

climbing equipment.

The grey

stakes are the super pitons that were placed in the turf of the grass slopes.

Top right is a selection of home made pitons, notice also the secateurs and steel carabiners.

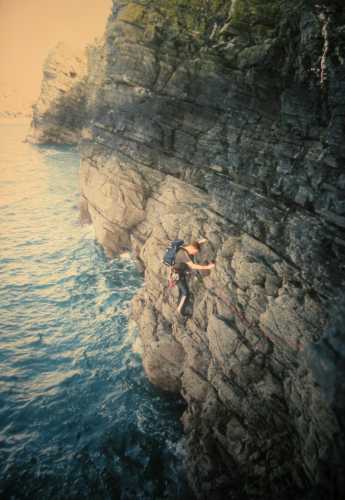

Cyril

during the 1970,s and found a man free of the constraints of modern climbers.

Often solo he climbed in big bendy boots across walls that many would consider

to be HVS+ today. He would not have even considered buying rock boots that were

on the market. He graded his routes as Easy, Moderate, Difficult and Hard. His

way of descending the cliff was to place a stake or piton then tie one end of

the rope to the anchor and the other end to himself. Should he fall then he

would stop after 120ft, hopefully short of the water where he would sort the

problem out. Normally he would descend the length of the rope, untie and solo

the remainder of the descent. He was an inspiration to those who at the time

felt that the direction of climbing was being dictated by trendy magazines,

equipment manufacturers and armchair climbers obsessed with grades and ethics.

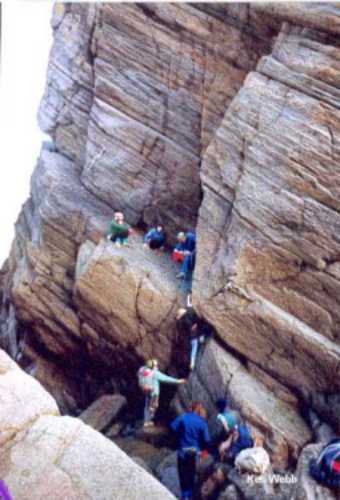

climbing on the Exmoor

coast. He occasionally shows these at local venues under the title of ‘The

Hidden Edge Of Exmoor’, which is also the title of a book he has written on the

subject. The majority of slides copied onto this site are his. He continues to

lead groups into the inaccessible sections keeping the access routes open,

finding new routes and replacing the rusting super-pitons as Archer named them.

He informs each party that more people have orbited the earth than have been

where they are now standing. This is probably true. In this modern climbing

world with all its hype and shiny pieces of equipment it is refreshing to watch

Kes at work on the traverse. His methods are identical to those used by Clemmy

and Cyril, unchanged over 40 years. Kes and his wife Liz recently took part in

an ITV production to celebrate 50 years of The Exmoor National Park. It was

called The Hidden Edge of Exmoor. Well worth a look if you can find a copy. You

can get a feel of the place from your armchair.

The Police Cadet Training Centre at Taunton. I met and

commenced climbing with Cyril Manning on The Exmoor Coast and quickly realised

that I would have to adjust and ignore quite a lot of what I had been taught if

I was going to keep up with this man who was older than my father. It dawned on

me that Cyril’s technique was not bred out of ignorance of basic safety

measures but of necessity. The tide waits for no man. Here was a place of

awe-inspiring scenery with huge cliffs and massive waves and at best only a six

hour window in which to achieve your goal. Speed and knowledge was the key. I

quickly got up to speed but the development of my nerve when the tide had

turned and was threatening to cut us off was taking a little longer. With the

knowledge of more and more escape routes committed to memory I began to feel at

ease. Cyril told me of his adventures with Archer and how the route had been pieced

together over a 10 year period. He lent me one of the rare copies of Archer’s

guidebook. The Exmoor Coastal Traverse

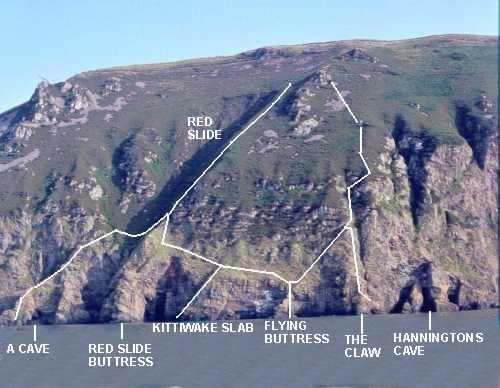

starts at Goat Rock, Foreland Point and finishes on the seafront at Combe

Martin. Only the section under The Valley of Rocks and a short distance from

Red Slide Buttress to The Claw beneath Martinhoe remained unclimbed. Archer

swam past both locations.

In early 1978 a very small intake of five 18-year-old

recruits arrived at the centre. A special training program had to be developed for

these older than normal cadets who would join the force within months.

The traverse was chosen as a project, which would have

all the usual fitness, adventure training and planning exercises involved. The

aim was to complete the traverse in one push carrying all the provisions and

equipment required without re supply or leaving the route. The route was to be

any beach or rock between the water and the grass line above the cliff. This

would mean not entering the water, and solving the two unclimbed problems

without climbing out onto the grass slopes.

The training went well and Cyril led us all around

Little Hangman and across the face of Yes Tor. The cadets nicknamed him ‘Kill

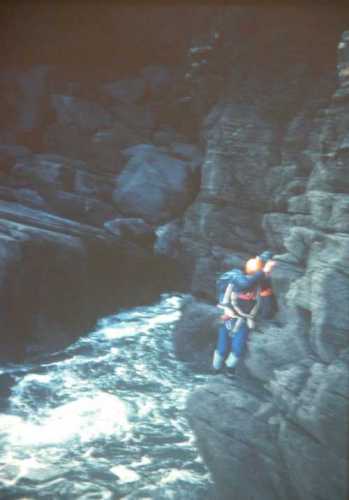

Me Quick’. The weight of our packs had been reduced to 30lbs and the cadets

were able to climb with the packs in bendy boots at a high standard.

At 4am on the 6th April 1978 we awoke and

travelled down to Foreland Point. Three had been selected to climb, two were

going to attempt to monitor our progress with a small vhf radio. No one, most

of all myself expected us to be successful, the aim had been reduced to ‘Lets

see how far we can get’. We were

allocated a week, I expected us to be somewhere in the Inner Sanctuary at the

end of the week having escaped and bypassed at least a couple of the difficult

sections.

The Start.

Goat Rock, Foreland Point. We were already in trouble. There was a large

swell, we were unable to start, we needed to be under The Valley of Rocks in

time to take advantage of low water that day, in order to cross the unclimbed

area. Foreland Point has strata leaning to the west, many of the reefs were

undercut and flooded on the west side.

Area of The Gun Caverns.

The Gun Caverns.

Pinnacle between Gun Caverns and Coddow Slip.

With the climbing around the point behind us, we were

able to walk along the beach with only the problems of Higher and Lower

Blackhead Points to slow us. Cyril was waiting for us at Lynmouth and wished us

the best of luck under The Valley of Rocks.

Our

late start had resulted in missing the low water under the Valley of Rocks. We

had arranged to meet our comms group just around the corner at Wringcliff Bay

that afternoon where we intended to camp. We were forced into serious climbing on

an incoming tide. We overcame the flooded east Inlet but came to a halt at the

large West Inlet.

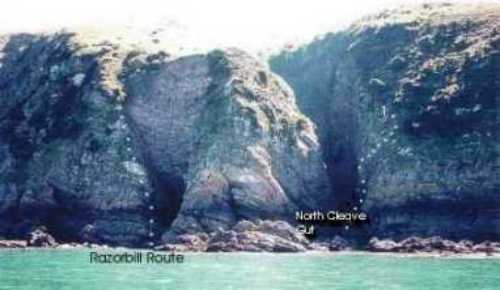

The two photos above show The Yellowstone area under

The Valley of Rocks. The North Walk footpath can be seen near the top of the

photograph. Inlets or Zawns are known as Guts in N. Devon. The larger one here

is The West Inlet or Mother Meldrum’s Gut as it is now known. We sat on the

ledges above the high water mark for 7 hours and waited for high water to pass

and the tide to recede back towards low water. The radio did not work. Because

of the need to reduce weight we could not carry water. We were relying on

streams and springs. It was bitterly cold, we could not sleep or cook. Darkness

came and at 10.30pm we saw the first boulders in the bottom of the gut. We knew

that this section from the Gut to Dog Hole on the other side was just over one

ropes length, but it was hard. We decided to go for it in the dark. With

torches clamped between the teeth we made our way across the last 200ft of cliff

at about 40ft above the water. It took us 4 hours. At 2.30am we walked into

Wringcliff Bay and woke our comms group who were asleep in the boulders, we had

been awake for nearly 24 hours.

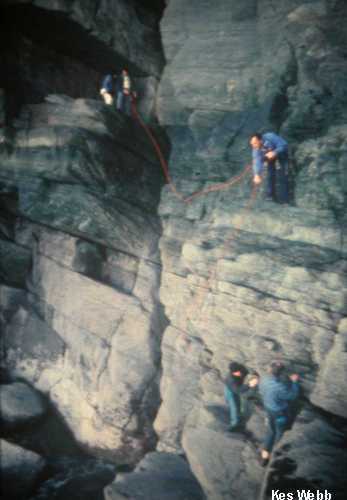

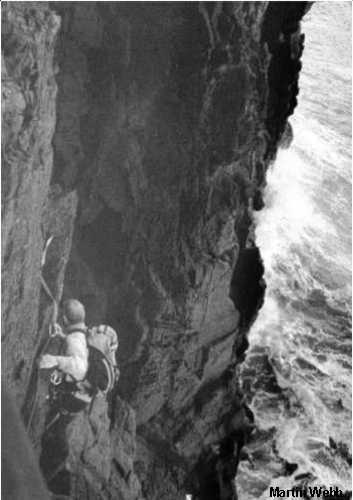

Traversing the walls of The East Inlet 1978.

The East Inlet as it was and is now. Ideally we would

have liked to have arrived here when the water was at this level. A climb along

the large ledge above and to the left of the climber was our intended route.

The photo to the right shows the inlet as it is now. Still a hard climb down on

to the fallen boulders then up the steep right wall with little protection.

Mother Meldrums Gut is the large Gut in the centre of

the photo. Our night climb took us across the cliff to the right of the Gut to

the first cave, Dog Hole. Note the high water stain across the cliffs.

East Inlet. Mother Meldrums Gut.

The

two Guts in the shadows are the East Inlet and Mother Meldrums Gut. Our night

climb took us across the wall to the right.

Myself in later years traversing our night route about 40ft up and still not above the high water mark.

Dog Hole. The point where we were able to descend back

down to beach level. Now the site of many high grade climbs put up by Martin

Crocker. High Magazine May 2000.

The following morning we had a conference on the beach

at Wringcliff Bay. Our plans were in shreds. We had climbed for one day and

were exhausted. Yes, we had cracked an unclimbed section but we were heavy and

moving far too slowly. We were using modern rope handling techniques with 3

x150ft ropes, which were wet and heavy, and a nightmare to sort out when the

four of us were on a cramped ledge. Reluctantly we had to accept that we would

have to climb on the low water at night and ditch two of the ropes one of which

we had already left in Dog Hole. This was later retrieved by Duncan Massey, a

local climber who was with the comms party. He was also trying to keep our

training Inspector calm. We had to

adopt Cyril Manning’s tactics or fail. We devised a system of having the leader

and last man climbing conventionally with belays and runners. The other two

made their way along the rope via ferrata style with two cow tails and had to

sort themselves out if they fell. As can be seen below there were times when

even this was abandoned for what later became known as deep water soloing. Our

plan for the second day was to traverse Duty Point, Crock Point, Woody Bay,

Wringapeak, The Three Bluffs and camp at the foot of Hollowbrook waterfall where

we would have a supply of water.

An

inlet called Duty Creek splits Duty Point. Clemmy had experienced difficulty on

the slabs on the east side of the creek because his nailed boots would not grip

on the smooth rock. We found it difficult on the steep west side where the

weight of our packs put unbearable strain on the arms and fingers.

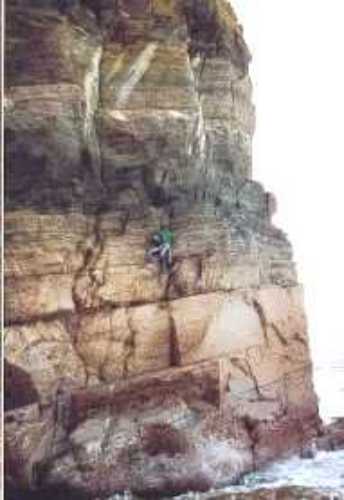

Woody Bay from Duty Point 1978. Crock Point is in the

middle distance to the left. The far distant coast starting above the head of

the climber on the right is, The Inner Sanctuary and the start of Kes Webb’s

Hidden Edge of Exmoor.

Crock Point. 1990,s Woody Bay

Waterfall 1978.

Wringapeak.

Wringapeak Cave.

Wringapeak Cliffs.

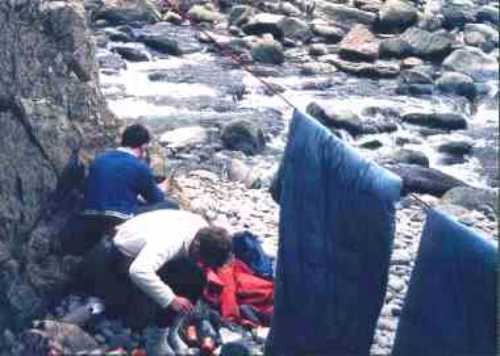

Big Bluff. Second Camp. 1978. We made it to Big Bluff,

the first of three without incident. Cyril had told us that at low water we

could descend down into a cave that ran through the bluff. We had arrived a

little after low water and could not find the cave entrance. Years later I

discovered an easy line across the face of the bluff which did not require the

tide to be so low. Again water was the problem. We had failed to reach

Hollowbrook Waterfall. We had to collect drips from a spring above to cook the

evening meal. We eventually found the cave entrance part way up the cliff, but

the sea could be heard 30ft down in the darkness. There was no way through. We

were about 200 metres short of our planned destination, Hollowbrook Waterfall,

and knew that we would have to make up that distance on the next low water at

midnight. We settled down in the boulders and slept.

The Inner Sanctuary.

The Three Bluffs from the Goat Track 500ft above. The

dark square entrance to the cave on Big Bluff is easily spotted from above but

not so easily found at beach level.

The Three Bluffs. Big Bluff. Double Bluff. Great Bastion. Serious country. Note the high water stain and the cliffs behind. Not a place to be caught on an incoming tide. On the 26th January 1964 Cyril Manning soloed The Diagonal Route up these cliffs to the footpath. 26th March 1996 Jon Denovan-Smith and I set out on a routine traverse from Wringapeak to Heddons Mouth. Sea conditions worsened as we were climbing across the face of Big Bluff. We were forced to climb higher above the water and in doing so established a high traverse through the bluffs. It took us three hours to reach Hollowbrook waterfall where we found Kes who had soloed down to check on us. The tide was by now incoming and very rough. We escaped up the waterfall with Kes. I mention this because no matter how familiar you are with these cliffs you cannot guarantee that you will achieve your aim on any one day.

Double Bluff and Gt Bastion with Hollowbrook waterfall

behind.

Great Bastion.

Cormorant Rock and The Yogi Hole. Jon climbing out of

The Yogi Hole on the west corner of Great Bastion. As can be seen from the wet

rock the spray was at times well over our heads.

Cormorant Rock. ( Low water). Navigation can be difficult. Direction of travel is

easy; keep the water on your right when climbing west and on your left in the

other direction. Being able to pin point your position is far more difficult. I

don’t know if a GPS would work in under these north-facing cliffs. Cyril had

told us to look out for a feature that resembled a horse’s head rearing out of

the water. This would be Cormorant Rock and hidden behind it would be

Hollowbrook Waterfall.

Cormorant Rock, heavy swell. Hollowbrook Waterfall.

At midnight we dropped into the cave through Big

Bluff. We could hear the sea in the darkness but we landed on firm ground. We

ran through the length of the cave and to our relief we found ourselves on the

dry beach between Big Bluff and Double Bluff. This was it, we were committed to

1500 metres of traverse which had the reputation of being hard, and at that

time only two known escape routes. Luck was with us, we were able to walk

through the cave which divides Double Bluff and along the reef to the beach

between the bluff and Great Bastion. Great Bastion had to be climbed. It is

about 220ft high and has a frontage of about 75 metres. We had been advised to

cross it at about 30ft. As we found to our cost the rising strata tends to take

you up far too high, especially in the dark. Having descended and located the

correct line we found it to be an agreeable climb apart from one small

bottomless recess in the middle of the face. Here the swell tended to be thrown

much higher than normal. We passed through The Yogi Hole at the NW corner and

immediately heard the roar of Hollowbrook Waterfall above the noise of the

swell. Having already eaten on Big Bluff we settled down for the night. It had

taken us less than an hour.

At first light we awoke and from our sleeping bags

gazed up at the source of the noise that had been dominant throughout our

shallow sleep. It was huge, Archer put its height at 186ft. The volume of water

pouring over the top of the cliff was way out of proportion for a small stream

that rose a short distance away at

Martinhoe. We walked out and climbed the broad back of Cormorant Rock and

immediately had a view of the difficulties ahead. The ominous Black Wall

totally blocked the route about 300 metres ahead. We were now in our third day

and much further ahead than I had thought possible. We were only using the rope

when there was the possibility of a serious fall, even then the whole party

would tend to be mobile while roped, providing we had at least a couple of good

runners between the leader and the last man.

The

Black Wall. Crossing Pharoahs

Chimney. The A Cave

It was now well over a day since we had any contact

with the others and knew that they must be concerned for our welfare. But there

was nothing we could do, the coast path was not in view and the radio required

line of sight in order to function. We made it to the foot of the Black Wall

one hour before low water. We climbed the strenuous 60ft overhanging corner

crack, come chimney, on the left side of the wall at severe grade. We later

discovered that this was a first ascent. Easy scrambling brought us to the

unmistakable A Cave with its rock bridge joining the main cliff to a flying

buttress.

The line of Pharoahs Chimney. HVS 5a.

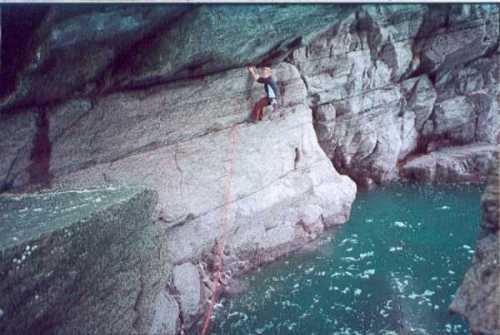

It was low water and the sea was calm. We were able to

scramble under the bridge and climb onto the wall of the main cliff. We

continued west un-roped across the gap of what is now known as Pharoahs Chimney

and down an easy slab to the beach on the east side of Red Slide Buttress. Here

we paused, and stared at the east wall of the buttress. It was un-climbable,

but Cyril had told us that only The Black Wall, The A Cave and the climb onto

The Claw would give us problems. One of the cadets wandered into a cave in the

back corner of the inlet and came running out shouting that he had found a way

through. We passed easily through the cave behind the buttress and came out

facing Archer’s Corridor Route, a swimming route through a cave under The

Flying Buttress.

The A Cave.

The Inner Sanctuary.

The Corridor Route.

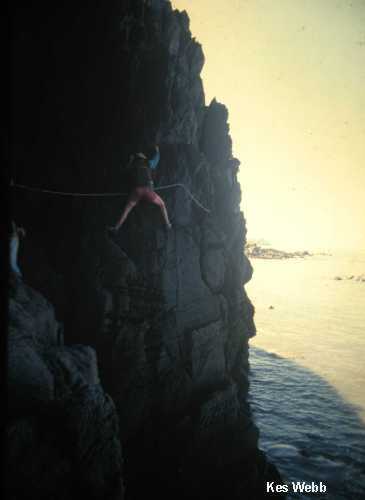

We were in a place where only a few people had stood,

when we heard “Hello” from above.

Nonchalantly perched on a narrow ledge 40 ft above was Cyril, tied on

the end of his rope which disappeared up over the grass line. While he was

explaining that people were getting anxious Pete Hopkinson, an Instructor from

the same centre came alongside in an inflatable. He took the below photo of us

crossing The Claw 40ft above the water. Cyril is stood on the far right on the

white rope.

Traversing The Claw. 1978

The Claw and Hannington’s Cave.

Two and a half days from the start in the far

distance.

Climbing The Claw from Hannintons Cave.

Same location as above, flooded this time.

Clinnocks Hole, a few metres west of Hanningtons Cave.

We bid farewell to Cyril and Pete informing them that

we would camp that night at Heddons Mouth, one of the few places that can be

reached by walking in from the road. The tide had turned. I knew that we had

about two hours to get there over 650 metres of boulders followed by a climb

around Highveer Point. Cyril informed us that he would see us in Combe Martin.

He appeared to believe that we were going to make it. We had a quick look

around the famous Hannington’s Cave then made off across the boulders of Bloody

Beach as Archer had named it. Here and there Hannington’s paths could be seen

on the slopes above.

Pimple Rock. East side of Heddons Mouth.

At the west end of Bloody beach is Highveer Point. It

can be walked on the low water of some spring tides but we were now two hours

into flood tide and the point presented a strenuous almost out of reach

mantelshelf move followed by a climb to the top of Pimple Rock. Once there, it

was a gentle stroll down the back of the rock onto the beach and a reunion with

the others.

Heddons Mouth.

It was still cold as it had been throughout the

previous three days. We discussed communications and decided that being above

us was of no use. The comms group would have to drive to some place where they

could almost achieve line of sight into the shoreline, and give the radio a

better chance of working.

After they had left, presumably to the Hunters Inn Hotel a short distance upstream, we set about cooking a meal and drying out our sleeping bags. These were damp from the condensation caused by the plastic survival bags. We were extremely tired and not talking much. One of the cadets said, “You know we are going to crack this”. Ahead lay The Swim, North Cleave Gut, Yes Tor and Little Hangman. They had already been around the last two with Cyril Manning. Pete Hopkinson and I had taken them down into North Cleave Gut, which had not gone well. They had not seen The Swim at West Lymcove where Clemmy had his accident. Quietly I thought, yes its possible, we had got further than I thought we would. It was cold but it was dry and the sea was calm. If it stayed that way we were in with a chance of success. As I was placing a piton to support the washing line I thought that it could be something small that would defeat us like a twisted ankle or some other injury, we were vulnerable because we were tired. It was at this point that I struck my thumb with the peg hammer.

Tuesday Route. Peters Rock top left. This feature, a few hundred metres west of

Heddons Mouth was frequently used by Archer and Agar for access and escape.

1955.

Ramsey Point to The Coxcombe. The Swim at West Lymcove

Point is located beside the lower exposed reef shown above. Archer fell here 7th

July 1965 descending to complete his amphitheatre climb which he had named The

Horseshoe Route. He was 69. The route follows the rim of the huge depression

above, which is filled with the shadow of its west ridge. Kes and Tim Webb

completed the route. Archer questioned them closely to ascertain if they had

stayed on route. He seemed satisfied when they mentioned finding discarded beer

bottles on the ridge?

The Coxcombe Ridge sweeping down from the grass line.

The Swim. West Lymcove Point. The Swim is an inlet,

which is always flooded. Initially Archer and Agar swam across the 5 metres

width in 1955 believing it to be un-climbable. Cyril soloed the route in November

1963 and led Archer across it during February 1964. He was surprised how easy

it was.

The Swim.

A few metres west of The Swim.

The Coxcomb Ridge. West Lymcove Point. This ridge is

less than 2ft wide at its narrowest point. The Swim is below the far end of it.

There are escapes each side of its neck, Coxcomb West and East. It was down the

grass slope of Coxcomb East that Archer fell. It was a wet day. He was

descending using a prussic knot on the rope for protection. He slipped and

grabbed the rope above the knot causing it to fail. He dropped 20ft to the

beach breaking his leg. Luckily he was not alone this time. Cyril was present.

Other than being killed this is probably the worst scenario one can imagine on

The Traverse. Here was a well built 69yr old incapacitated on a tidal beach at

the foot of an 800ft cliff. Cyril climbed the cliff three times that day

ferrying Dr Mold and The Fire Service to the scene. The Fire Service lifted

Archer out with an 1100ft combination of rope and fire hose. It was an

agonising eight and a half hours before he arrived at Barnstaple hospital.

Coxcomb West Gully. 200ft . Low water. Not an easy

escape route

At Heddons Mouth we had a leisurely start to the day.

High water that morning was 9.8 metres. We could not move west until about

10.30am. We moved quickly, un-roped along the tops of the reefs past The

Tuesday Route and were soon getting our gear on for The Swim. The climb went

off without incident and we were soon motoring towards Bosley Gut where a short

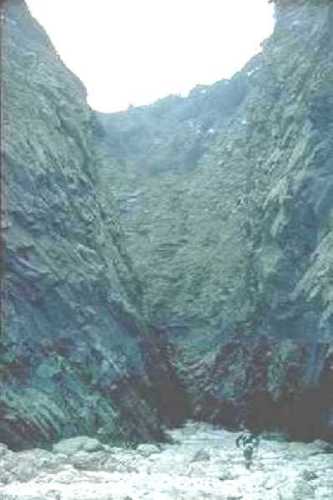

climb around the corner brought us onto the beach leading to North Cleave Gut.

We had been here before and knew what to expect. We were surprised to find that

the tide was exceptionally low and we were able to walk into the gut. It is an

awesome place. Archer describes it as being an inlet of the sea, which at high

tide runs up a channel for 120 yards, and most of that distance is less than 10

yards wide. Sheer walls of 250ft on the east side and nearly 400ft on the west

side dominate the inlet. At the back of the gut in the east corner a waterfall

drops 350ft in a horizontal distance of 50ft. I was 30, I would not have

believed that 25yrs later I would be still climbing and Martin Crocker would be

dragging me up routes on the massive west wall.

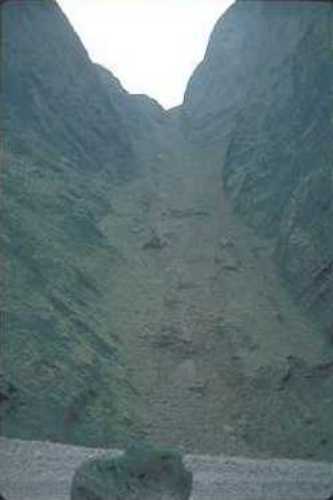

North Cleave Gut.

North Cleave Gut. 1978. Graham Rodgers going off in search of water, and the huge west wall.

North Cleave Gut. To move west this usually has to be

climbed. This time the weather was much calmer. The blow holes in the cliff

were not operating.

Mare and Colt pinnacles from North Cleave Gut.

Sherrycombe Waterfall.

A WWII U Boat frequently took on fresh water here. No

chance of being found under these cliffs.

Sherrycombe Waterfall.

Sherrycombe Waterfall. 1978 Great Hangman Gut. 800ft.

By mid afternoon we had reached Sherrycombe Waterfall

and drank heartily. I had expected this to be our 4th camp but the

tide was still way out. Was there a chance we could force another 1500 metres

to Yes Tor? We decided to go for it. We could always spend the night safely in

the bottom of the Great Hangman Gut, which was about halfway.

Great Hangman Gut.

Yestor. Never a beach, always has to be climbed.

Clare Tryon and Pete Wells on the High Traverse of Yes

Tor. Different sea conditions.

The Great Hangman Cliffs, Englands highest. Area of

camp 4.

We passed the bottom of The Great Hangman and out onto

Blackstone Beach without climbing. The tide had been coming in for an hour yet

the beach was still clear. I had never seen it so low. Within twenty minutes we

were at the east side of Yes Tor, the stepping-stones leading onto the face

were still above water. We stepped casually onto the face where before we had

to wait and judge the time to run and jump between the waves. I was getting

crazy ideas about finishing the route in Combe Martin that night. We reversed

the route across the face that Cyril had shown us a couple of months earlier

and came out on the ramp at the foot of Yes Tor Ridge. We saw the swell hitting

the reef ahead at the foot of Little Hangman and decided we had done enough

that day. When we left Sherrycombe Waterfall the question of availability of

water did not cross our minds. Yes we had made it a little further than

planned, but the cost was going to be another cold night without food or drink.

We tried the radio and could faintly hear the others calling but they could not

hear us.

Little Hangman Cliffs. To the right is The Gritstone

Wall mentioned in climbing guides.

Little Hangman Gritstone Wall climbing area.

The East/West Cave. The spur of rock with water each

side is The Ramp. The seaward side is vertical, the other slopes gently to the

beach at low water. The traverse makes its way along these vertical cliffs

until it is possible to climb up onto the Ramp. Martin Crocker has put up a

number of routes here including one called, ‘He Sang In His Chains Like The

Sea’ The line ascends the wall to the right of the cave then left across over

the entrance before heading up to the grass slope.

The face of The Ramp, East/West cave. 1978 Black Chimney,

sea inlet.

The morning was grim. It was cold and we wanted to end

the trip asp. As can be seen below the sea had become angry with white horses

visible. We got moving far too early, the water had not receded far enough. We

made our way easily across the beach below Little Hangman Gut but ran into

difficulty as we edged along the cliff towards The East/West Cave. The swell

was striking the cliff and climbing up towards us. As can be seen above the

climb onto The Ramp did not look too good. It took us well over half an hour to

Climb over The Ramp, down into the gully behind and up onto the large ledges

leading to The Black Chimney. Here the gully into the chimney was flooded. At

low water the corner on the west side of the gully is difficult to climb with a

pack. We stood around waiting for the tide to ebb and it began to snow.

Balclava’s and hoods were pulled over our heads as we stood and stared at the

Scotch stone reef a few yards off shore. Eventually we were able to cross, I

recall that we had not considered the problem of barnacles. Our hands were

scratched and cut. They stung from the wet and cold. A couple of weeks later we

all noticed that the skin on our hands began to flake and peel.

Little Hangman 1978. The Scotch Stone Reef.

A recent photo of the reef in calmer weather. Note the HW

stain.

The final corner. Camp 3 in the far distance.

Cathedral Cave. Stepping Stones Cave.

The Hangmans and cliffs towards Heddons Mouth in

winter.

We arrived at Combe Martin during the morning of the

10th April 1978. It had taken us four and a half days. There was no

sign of our comms group, the local Bobby took the photo below. We had stayed on

our intended route between the water and the grass line and no one had taken a

fall. As far as I know the route has never been repeated in one push, and never

done west to east in one go.

I have been asked how it is that the early pioneers took 10 years to complete the route and yet it only took us less than a week. First of all we were very lucky with the weather and tide, better equipped, younger and with the exception of Cyril Manning much fitter. We used the low water at night so you could argue we took the equivalent time of nine good spring tide days. To equal that the old timers who only went out on one spring tide a month would take nine months, and of course bad weather or lack of a climbing partner would stretch it well beyond a year. We had no route finding problems, they had already done the time consuming work for us. They would attack a difficult section from both ends on different days always turning back when the tide turned unless they could see the final point of a previous visit. This at one day a month took years. They did other things like the exploration of Baggy Point, sketching and mapping, placing stakes for anchors on the escapes, which also would have to be cleaned. Including the planning and recce’s it actually took us 3 months. If you include my experience on the Exmoor cliffs over the years and the knowledge gained that was put to use on our trip, there is little difference.

The real reason is we wanted to do it when they would

have thought, “Why”? I have no doubt that if Cyril Manning wanted, he would

have soloed the entire route in two to three days, counting the birds and

collecting minerals as he did so.

I am asked what grade is The Traverse? Cyril Manning

would have replied that it varies between easy and hard. I don,t know, we found

some VS sections but we had good weather and stayed reasonably low. If you are

forced up higher into exposed positions where the tide has not cleaned loose material from the cliff I cannot say

what grades you may encounter. You may have it easier than us and be able to

walk past some of the difficulties and wonder what all the fuss is about.

Weather and tide on the day dictates the line.

Very few climbers have enquired about The Traverse.

Sea canoeists have been keen to locate the through caves so that they can

paddle through on the high water of spring tides. The main interest today is

from those who go Coasteering. It would seem that the clock is being turned

back 40 years to Clemmy’s aquatic era. Before long on the coast path someone

may report sighting individuals in wetsuits, helmets, and life jackets hacking

their way up the slopes with an iceaxe.

The 1978 Team.

Robert

Simmonds. Graham Rodgers. Trevor Simpson. Terry Cheek.