I took an interest in him partly because I saw from the report in the paper that he'd been an inpatient at Hairmyres Hospital on a ward run by a consultant psychiatrist who happens to be one of my oldest friends, though he wasn't actually her patient.

So I read up on the court-case against him, including his own writings about it. I was impressed by his powerful, compressed literary style, and was convinced by the evidence that the offences of which he had been convicted were extremely minor.

The offence of possession of illegal pornography was certainly unconnected with his own sexual behaviour, since even the prosecution stated that it had been committed only under extreme duress: and even if he was guilty on the other charges they were the result of what the court called vulgarity and I would call juvenile masculine bravado, rather than serious perversion.

I took Eric up as a sort of research project, and became further convinced that he was telling the truth when he said that the only offences of which he was guilty were committed under duress, as part of the atrocious abuse to which he had been subjected; and that he had been pressurized into pleading guilty falsely to what the Crown later acknowledged were extremely minor charges of lewdness and indecency, at a time when he was too ill with depression to argue.

This view was later confirmed by his psychiatrist Dr Prem Misra, one of the top experts on sex offenders and their victims in Britain, who has stated publicly that Eric showed no trace of any sexual perversion whatsoever. It was not that I believed Eric's version of events because he was my friend: he became my friend because I believed him, on the strength of good evidence.

I was deeply impressed by and interested in him: not as an object of pity but because I saw that even though he had suffered so much it was almost beyond comprehension, it hadn't dented either his compassion for others or his sense of humour. Clearly, he had great strength of character.

Equally clearly, he had suffered immense psychological damage. He was far from isolated, since he had a very loving and supportive adoptive family and many close friends; especially the McFarlan family with whom he lived during the period of the court-case, and who saved him from suicide. However, when someone has suffered so much cruelty they need as much loving support as they can get to help them come through it. I already had considerable experience helping friends who had been abused sexually and/or physically, and I knew that I had skills which could be useful to Eric - in particular to help shore up his shredded self-esteem.

So I wrote to him - a few supportive but short and slightly impersonal letters, because after all we were strangers. Nevertheless he was constantly in my thoughts, and even at this stage I felt so much in tune with him that like a twin I could pick up on his emotional state.

For a long time I didn't know whether this "tuning-in" effect was real or just my imagination, but later, once Eric and I had become friends and were in regular communication, he was able to confirm times and dates on what I was sensing from him, well beyond any possibility of coincidence. Indeed I realized that I had been doing so since several months before I consciously heard of him, beginning in January 1995 when he had had his second acute nervous breakdown and had been experiencing - and broadcasting - violent emotional distress.

Irrespective of whether you believe that this is possible or just some mutual delusion, it is a fact that Eric himself believed that I could to a considerable extent overhear what was in his head. It is significant, therefore, that when I asked him whether he found this idea alarming or comforting he replied "Oh, comforting!" with some force. If he had had any major guilty secrets, he would have found it terrifying.

Eric was released from Barlinnie after fifteen days, pending an appeal against sentence. He was petrified of going back to prison: between "picking up" his fear and my own fear for him, I couldn't settle for worrying about him, so I came to hear his appeal. The press was predicting a massive demonstration against him, and a colleague at work said I'd better not go because it sounded as if it could get nasty: I replied that the more enemies he had there the more he would need supporters.

|

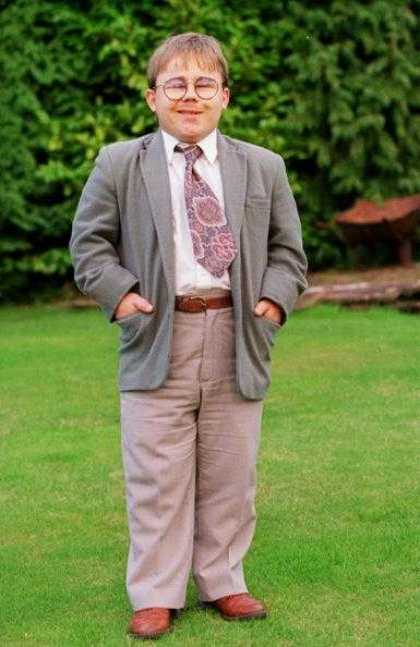

Probably taken after the appeal, as he only seemed to wear a suit for court (standard Scottish joke: "What do you call a Glaswegian in a suit?" "The accused.")

|

In the event the threatened mass demonstration consisted of three strange women who seemed to be on drugs. This actually wasn't very funny because they were verbally and physically aggressive and were trying to get close to Eric to make their presence felt, but I planted myself in their way and refused to shift - so I was able to spare him an additional source of distress.

Afterwards I saw him coming down the corridor and I said "Congratulations". He could have just said "Thanks" and walked on: but even though he had been so terrified that he was completely white even to his fingernails, he stopped and spoke to me with a warmth and emotional openness which was characteristic of him.

He finished by giving me a hug and a kiss, and in hugging him I felt more closeness towards him, less barrier between him and me, than with anyone else in my life. I asked if there was anything I could do for him and he said "Write to me."

So I wrote to him, putting everything I knew into making him feel better about himself, and into giving him something witty to lift his spirits because I knew how important laughter was to him - long chatty personal supportive letters every three weeks for seven months without an answer because he was too ill with depression to answer. And then in May he was finally well enough and he wrote to me and he 'phoned me and told me I had been "a great source of strength" to him. Because he was still quite depressed at that time I didn't hear from him again until late June - and then suddenly we were speaking to each other every few days, more often than I was in touch with any of my other friends.

The whole of our two-way conversation together added up to only a handful of hours, spread out over three months, and in a sense we hardly had time to get to know each other at all. Neither of us knew that the other could sing, or write poetry; I had to wait till his funeral to learn that he had thought of being a minister. Yet because he spoke with real emotion and openness - also so fast and so much to the point that he could get more of himself into a twenty-minute conversation than most people could into twenty hours - in another sense we had time to get to know each other very well: time enough to know each other's true characters. And he had more and better character than anyone else I ever knew - and was the best fun and the easiest to be with, despite all his suffering.

I knew so much raw horror about his life, but all the time we were speaking together we were laughing, and I told him he was the Cheshire Cat - that even if everything else were taken from him the grin would remain. The fact that he was "on the box" was a total blank to me: but as a nurse's son with a degree in Psychology he also had a place in my world, the NHS/academic world.

|

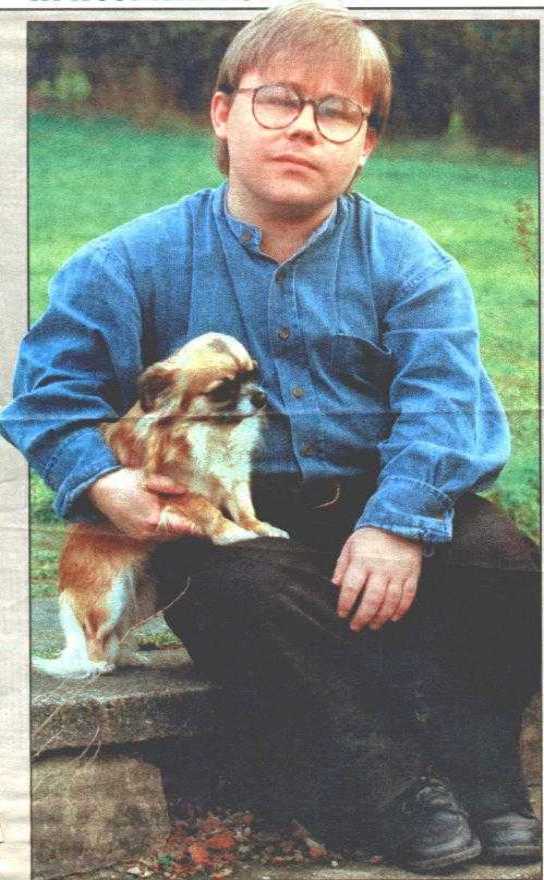

With Holly, the refugee from the puppy farm

|

I was interested in him rather than in what had happened to him. We barely spoke about his terrible experiences: not because he didn't trust me to know, since I was his second-favourite choice to accompany him the next time he went to give evidence about being abused, but because we were just friends, and talked about the things friends talk about - religion and politics, beer and birthdays and his plans for the future he would never see. He seemed more concerned about a friend of his who was going through a messy divorce, and about a friend of mine who had cancer, and his own little dog who'd been rescued from a puppy-farm where she'd never known any love, than about his own pain.

In any case, I consciously avoided any topics which might risk triggering one of his terrifying flashbacks - knowing that he was alone in the house, with no-one to help him if he panicked: and knowing that he had once taken an overdose under just those circumstances.

There were many things I would have asked him, things I would have said to him to help him to see himself in a better light, that I was saving until I would be in the room with him, so I could offer gin and sympathy if he became upset. But we were allowed no time for the long face to face conversations we had both planned.

We had time enough that we had already developed a history of in-jokes between us, even in the grimmest context. He was enchanted because I told him that my immediate reaction, on hearing how, in a paroxysm of desperation, he would sometimes beat his head against the wall until he bled, had not been "How tragic" but "How West Coast" (this is a joke which may not mean much to non-Scots: it has to do not only with traditional Glaswegian behaviours but with traditional Edinburgh attitudes to traditional Glaswegian behaviours - and what a "heid-banger" is and why East Coast Scots tend to think that all "Weegies" are it).

I saw how afraid he was of testifying in court against his abusers - and how determined to do it anyway, not for personal revenge but to protect other young boys from suffering as he had done. At a time when certain sections of the tabloid press persisted in calling him "shamed" and a "pervert" I was overwhelmingly proud to be his friend - not because he was famous and a TV-star, which I regarded as an irritating irrelevance, but because it seemed to me that he was the most wholly admirable person I had ever met.

This wasn't just my opinion: he really did have an extraordinarily attractive character, and many people who began by seeing him as an object of pity ended up personally devoted to him. He was kind and clever and funny, sensible, original and brave and absolutely individual: a shining young man - and an intensely Scots one.

I myself fell entirely in love with the man (for only the second time in my life: it's not something I make a habit of). Although we only knew each other for a year, and that patchily, our friendship was the defining relationship in my life, and by Eric's own account it was fairly important to him too. Certainly he had the highest regard for me. He told me my letters had been "a great source of strength" to him, declared that nothing else could be as witty as those letters, was embarrassingly impressed by what I do for a living (FoxPro programmer), and 'phoned me on the anniversary of his imprisonment, demanding "Cheer me up!". Which I did: he was the whole world's clown, but I was his.

I asked him once, idly, what he made of me - this strange woman turning up to support him - and he replied flatly "I think of you as a real light". There's no telling whether he and I would have ended up as an "item", but he had high expectations of our friendship - regarding me both as a source of unbiased advice and as someone he could get rowdy drunk and have a laugh with. I was going to teach him to use a "proper" computer (as opposed to his elderly word-processor), and introduce him to the pleasures of Real Ale and the spectacularly lethal cocktails drunk by Science Fiction fen.

A colleague told me I mustn't get actively drunk in his presence as "It's not ladylike and men don't like that", so I said to him "You don't want me to be 'ladylike', do you?" and he replied "Certainly not!". He gave me every reason to suppose that I had succeeded in what I set out to do for him, and that if I hadn't been around his mental state during the last year of his life would have been much worse than it in fact was.

I was stunningly happy - wandering about in a dream singing the traditional Scots song Plooman Laddies